Alternative and renewable fuels: There is life after cheap gas!

Some environmentalists believe that if you invest in and develop alternative replacement fuels (e.g., ethanol, methanol, natural gas, etc.) innovation and investment with respect to the development of fuel from renewables will diminish significantly. They believe it will take much longer to secure a sustainable environment for America.

Some environmentalists believe that if you invest in and develop alternative replacement fuels (e.g., ethanol, methanol, natural gas, etc.) innovation and investment with respect to the development of fuel from renewables will diminish significantly. They believe it will take much longer to secure a sustainable environment for America.

Some of my best friends are environmentalists. Most times, I share their views. I clearly share their views about the negative impact of gasoline on the environment and GHG emissions.

I am proud of my environmental credentials and my best friends. But fair is fair — there is historical and current evidence that environmental critics are often using hyperbole and exaggeration inimical to the public interest. At this juncture in the nation’s history, the development of a comprehensive strategy linking increased use of alternative replacement fuels to the development and increased use of renewables is feasible and of critical importance to the quality of the environment, the incomes of the consumer, the economy of the nation, and reduced dependence on imported oil.

There you go again say the critics. Where’s the beef? And is it kosher?

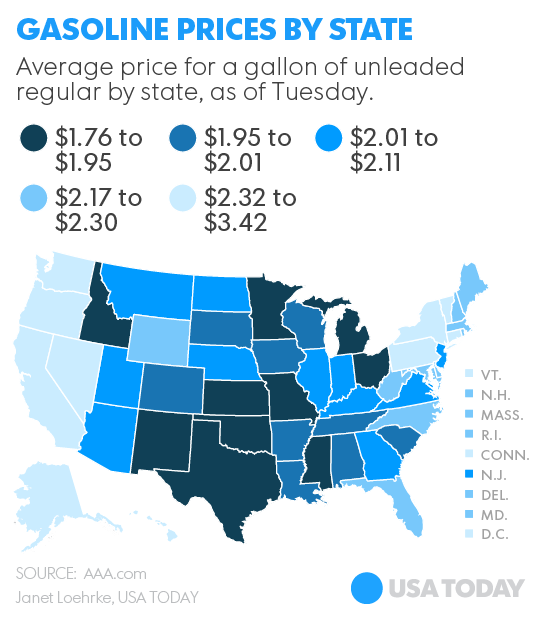

Gasoline prices are at their lowest in years. Today’s prices convert gasoline — based on prices six months ago, a year ago, two years ago — into, in effect, what many call a new product. But is it akin to the results of a disruptive technology? Gas at $3 to near $5 a gallon is different, particularly for those who live at the margin in society. Yet, while there are anecdotes suggesting that low gas prices have muted incentives and desire for alternative fuels, the phenomena will likely be temporary. Evidence indicates that new ethanol producers (e.g., corn growers who have begun to blend their products or ethanol producers who sell directly to retailers) have entered the market, hoping to keep ethanol costs visibly below gasoline. Other blenders appear to be using a new concoction of gasoline — assumedly free of chemical supplements and cheaper than conventional gasoline — to lower the cost of ethanol blends like E85.

Perhaps as important, apparently many ethanol producers, blenders and suppliers view the decline in gas prices as temporary. Getting used to low prices at the gas pump, some surmise, will drive the popularity of alternative replacement fuels as soon as gasoline, as is likely, begins the return to higher prices. Smart investors (who have some staying power), using a version of Pascal’s religious bet, will consider sticking with replacement fuels and will push to open up local, gas-only markets. The odds seem reasonable.

Now amidst the falling price of gasoline, General Motors did something many experts would not have predicted recently. Despite gas being at under $2 in many areas of the nation and still continuing to decrease, GM, with a flourish, announced plans, according to EPIC (Energy Policy Information Agency), to “release its first mass-market battery electric vehicle. The Chevy Bolt…will have a reported 200 mile range and a purchase price that is over $10,000 below the current asking price of the Volt.It will be about $30,000 after federal EV tax incentives. Historically, although they were often startups, the recent behavior of General Motor concerning electric vehicles was reflected in the early pharmaceutical industry, in the medical device industry, and yes, even in the automobile industry etc.

GM’s Bolt is the company’s biggest bet on electric innovation to date. To get to the Bolt, GM researched Tesla and made a $240 million investment in one of its transmissions plan.

Maybe not as media visible as GM’s announcement, Blume Distillation LLC just doubled its Series B capitalization with a million-dollar capital infusion from a clean tech seed and venture capital fund. Tom Harvey, its vice president, indicated Blume’s Distillation system can be flexibly designed and sized to feedstock availability, anywhere from 250,000 gallons per year to 5 MMgy. According to Harvey, the system is focused on carbohydrate and sugar waste streams from bottling plants, food processors and organic streams from landfill operations, as well as purpose-grown crops.

The relatively rapid fall in gas prices does not mean the end of efforts to increase use of alternative replacement fuels or renewables. Price declines are not to be confused with disruptive technology. Despite perceptions, no real changes in product occurred. Gas is still basically gas. The change in prices relates to the increased production capacity generated by fracking, falling global and U.S. demand, the increasing value of the dollar, the desire of the Saudis to secure increased market share and the assumed unwillingness of U.S. producers to give up market share.

Investment and innovation will continue with respect to alcohol-based alternative replacement and renewable fuels. Increasing research in and development of both should be part of an energetic public and private sector’s response to the need for a new coordinated fuel strategy. Making them compete in a win-lose situation is unnecessary. Indeed, the recent expanded realization by environmentalists critical of alternative replacement fuels that the choices are not “either/or” but are “when/how much/by whom,” suggesting the creation of a broad coalition of environmental, business and public sector leaders concerned with improving the environment, America’s security and the economy. The new coalition would be buttressed by the fact that Americans, now getting used to low gas prices, will, when prices rise (as they will), look at cheaper alternative replacement fuels more favorably than in the past, and may provide increasing political support for an even playing field in the marketplace and within Congress. It would also be buttressed by the fact that increasing numbers of Americans understand that waiting for renewable fuels able to meet broad market appeal and an array of household incomes could be a long wait and could negatively affect national objectives concerning the health and well-being of all Americans. Even if renewable fuels significantly expand their market penetration, their impact will be marginal, in light of the numbers of older internal combustion cars now in existence. Let’s move beyond a win-lose “muddling through” set of inconsistent policies and behavior concerning alternative replacement fuels and renewables and develop an overall coordinated approach linking the two. Isaiah was not an environmentalist, a businessman nor an academic. But his admonition to us all to come and reason together stands tall today.